The Hollow Core of Kerala’s Public Health Sector

Kerala’s public health model hides deep cracks.

Kerala often appears as the healthcare ideal: its infant mortality rate (IMR) has dropped to 5 per 1,000 live births, far below the national average of around 25, and its maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is down to 30 per 100,000 live births. But these numbers hide a truth: many of Kerala’s people turn to private hospitals even for regular care, which helps relieve pressure on government medical colleges. Without the private sector picking up so much slack, the public medical colleges would be buckling even more.

When I entered the medical field as an undergraduate student in the year 2012, only five colleges were in the government sector: Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode (Calicut), Kottayam, Thrissur, and Alapuzha. The Government of Kerala subsequently added seven more to its roster, and as of 2025, 12 medical colleges are operational in the state. However, except for the first five, the rest are lacking even the basic facilities. Institutions in Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, and Kottayam are still holding on, still offering relatively decent services. Alappuzha and Thrissur follow closely behind. But others, Kollam, Kannur, Manjeri, and Idukki, are frequently reported to be in bad shape: vacant faculty positions, poor equipment, non-functional tools, and stretched staff. The disparities are no longer marginal; they are systemic.

Idukki Medical College had even lost its accreditation due to a lack of facilities prescribed by the NMC. Konni and Palakkad are not more than a glorified outpatient department. In a state like Kerala, where the population density is so high, a fully operational medical college is required in each of the fourteen districts. As Wayanad and Idukki district consists largely of difficult terrains to travel, the inhabitants need a decent medical college for their heal needs. Despite this huge gulf in the availability of healthcare, Kerala is still managing to top the health metrics, and credit goes to private hospitals and clinics that made healthcare accessible.

The rising manpower crisis in public medical college hospitals is another concern. Faculty shortages, delayed pay revisions, and heavy workloads are now topics of protest, not whispers. The Kerala Government Medical College Teachers’ Association (KGMCTA) has warned of boycotts of teaching and outpatient services if their long-standing demands are not met. Whenever there is an inspection from the medical council, the existing faculties would get shunted to medical colleges like Idukki, Wayanad, Konni, etc, to maintain the standards. Instead of filling new posts and strengthening the system, this measure has only robbed Peter to pay Paul, weakening the parent institutes further and shrinking the services they were already struggling to provide.

A telling incident involved Dr Haris Chirakkal, head of Urology in Thiruvananthapuram Medical College. He publicly revealed that surgeries had to be postponed because essential surgical implants and tools were unavailable. For patients without means, that delay is not just an inconvenience, it’s real harm. Rather than fixing the supply gap, the government responded with a show-cause notice to Dr Haris. An expert committee was formed, but what worries people is whether the promised action will follow.

Meanwhile, pay anomalies persist. Entry-level assistant professors argue that their salary is unreasonably low, making government posts unattractive. A gastroenterologist, who completed his/her DM, will earn anywhere between 2.5 and 4 lakhs in a private hospital. Now compare that to the entry-level pay in the Kerala Medical Colleges. Many doctors face delayed promotions and outstanding arrears from past years. Temporary transfers and staffing gaps throw off both teaching schedules and patient service. In medical colleges like Konni or Idukki, the shortage is acute enough to degrade everything from OP capacity to inpatient care.

Also adding to the cracks is the problem of surgical equipment and supplies. In recent months, the state government has allocated ₹100 crore to resolve hospital supply crises caused by unpaid dues to drug and equipment suppliers. Surgeries at major colleges (Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode) have already been disrupted because firms have refused to deliver until arrears are cleared. Some colleges are sourcing essential items at inflated costs to compensate.

An opposition report calls the state’s system “cracking at every joint.” It states that flagship programs like Aardram Mission are stalling, new facilities remain under-utilized due to lack of sanctioned staff, diagnostic services like MRI have long wait times, essential surgeries are being done under torchlight in some cases, and drug shortages are common. The famous “Kerala model” in public health is being exposed as less stable than assumed.

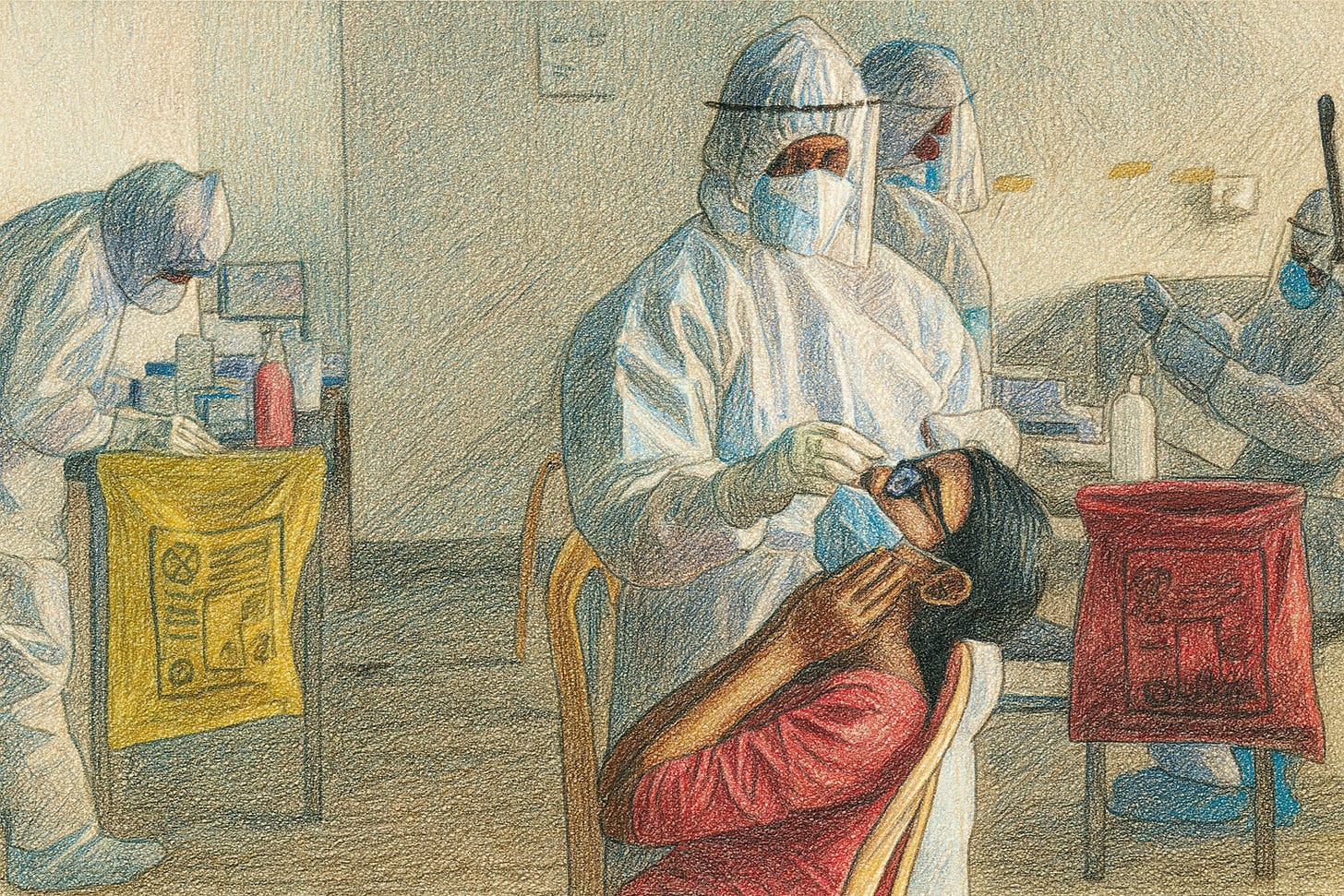

So yes, Kerala has non-trivial successes: low IMR, reduced MMR, strong literacy, good awareness, and health-seeking behaviour. Kerala has also shown flashes of remarkable resilience in the face of public health emergencies. When the Nipah virus struck, the state’s rapid contact tracing, strict isolation protocols, and community-level awareness campaigns drew international praise. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kerala initially managed to flatten the curve effectively through early surveillance, strong local body interventions, and efficient use of its primary healthcare network. Unlike many other states, Kerala did not face an oxygen crisis even at the peak of the pandemic. These achievements underline that Kerala’s strength lies in its preventive and community health mechanisms, even though its hospital infrastructure continues to show cracks. The structure underneath, public medical colleges, public hospital equipment, faculty numbers, and fair pay, are under strain. Without urgent corrective steps, what looks like strength might reveal itself as fragility.

Nevertheless, the crisis is not unsolvable, but it needs a strong political will and administrative discipline. First, the government must stop the practice of shifting existing faculty around for inspections. Instead, sanctioned posts should be created and filled in every college, especially in Kollam, Kannur, Manjeri, Idukki, Konni, and Palakkad. Robbing one institute to save another only weakens both. Second, the pay anomalies must be corrected without delay. Nobody can expect a young specialist, after slogging for over a decade in training, to accept a salary that is a fraction of what private hospitals pay. If the state wants good teachers in its medical colleges, it must match pay with responsibility. The state has the resources, but it needs to be allocated judiciously. One such example is the pension scheme for the personal staff of ministers, where individuals become eligible for lifetime pensions after just two years of service. This highlights how political decisions can sometimes create financial imbalances.

Third, procurement has to be streamlined. The incident with Dr Haris Chirakkal exposed how even flagship colleges like Thiruvananthapuram fail to keep surgical tools ready. Essential drugs, implants, and machines should not become bargaining chips between suppliers and the government. Clear budgetary allocations and timely payments are basic, not optional.

Fourth, infrastructure has to be strengthened district by district. In a state with such a dense population and difficult terrains, every district deserves a fully functional medical college. Half-baked OP-style colleges only create the illusion of coverage.

Fifth, accountability and transparency must improve. When services collapse, blaming doctors is easy, but it solves nothing. There should be public audits of faculty strength, patient load, and equipment availability in every government college. People deserve to know what is missing and why.

Finally, the state has to rethink its health model. Kerala cannot go on relying on private hospitals to cover up the cracks in public institutions. Equity demands that government hospitals remain the backbone. Without serious investment in manpower, infrastructure and fair pay, the so-called Kerala model will remain a mirage, strong on paper but weak on the ground.